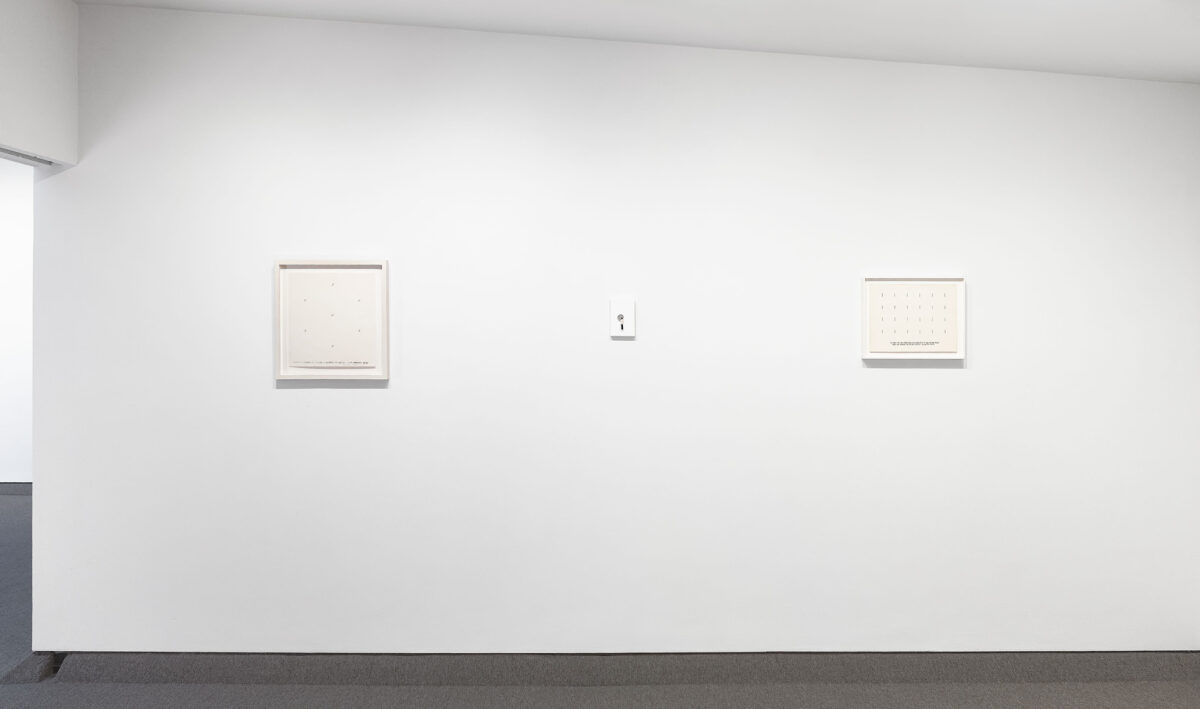

The current exhibition features works by Douglas Huebler and Liliana Porter. Both artists use reduced visual means to explore ideas of assumption, connection, extrapolation, and imagination, and, for each artist, humor plays a key role in beckoning viewers to explore, participate, question, and wander.

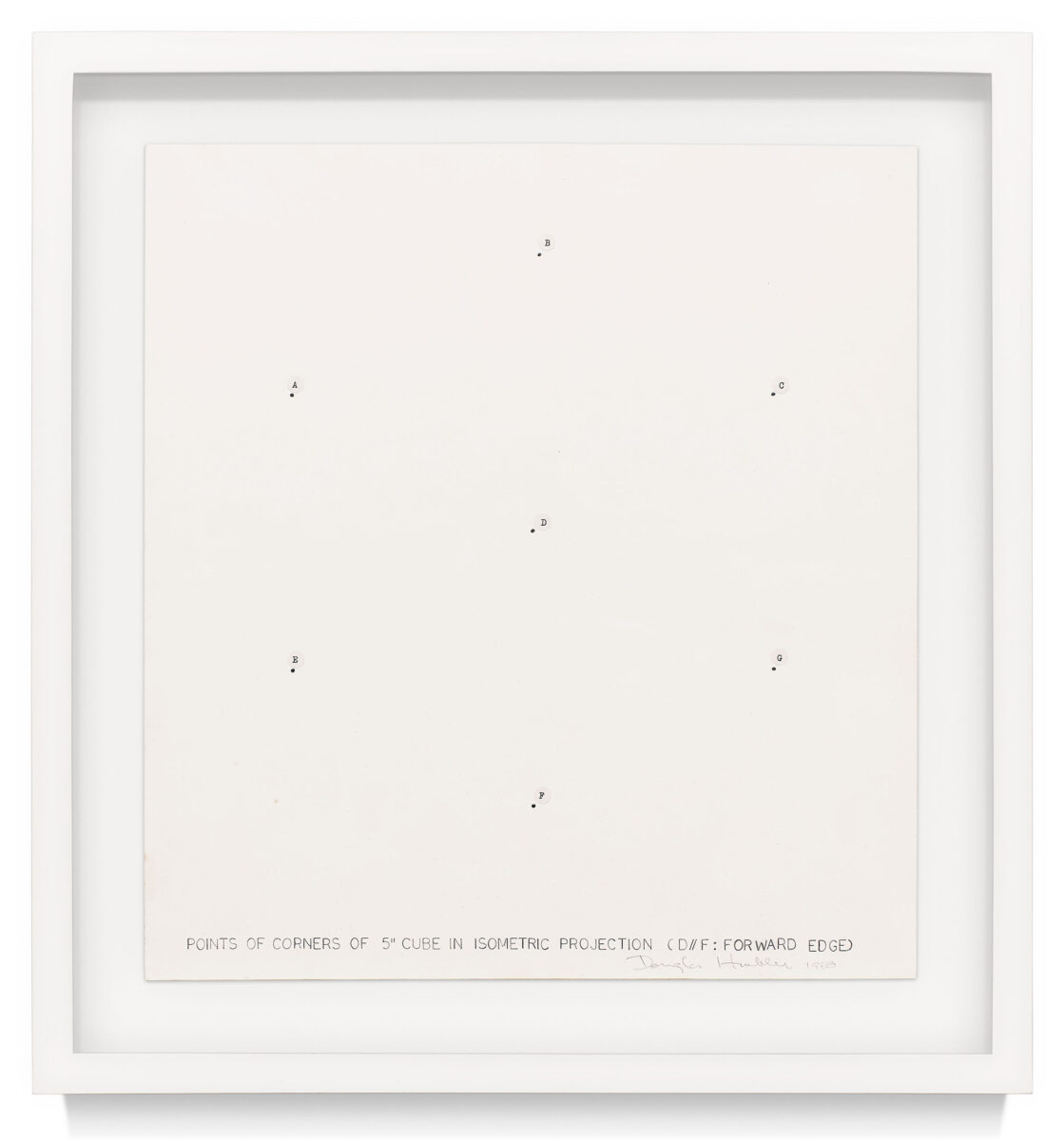

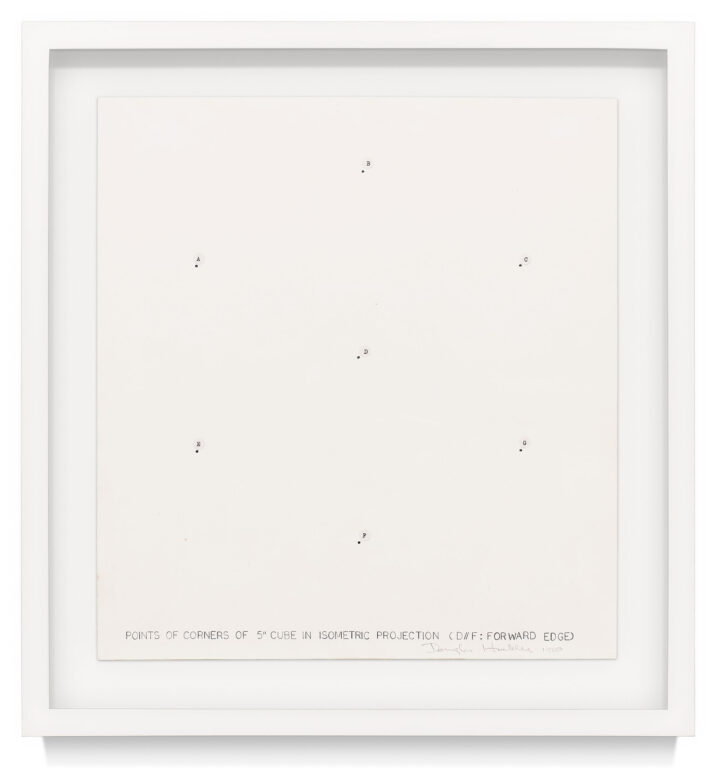

Douglas Huebler (b. 1924, Ann Arbor, Michigan; d. 1997, Truro, Massachusetts) came to prominence in the late 1960s and early 1970s for making visual work that combined photographs, drawings, and/or maps along with written texts (as captions or descriptions of a process, structure, or system that relate to the imagery). Huebler created visual experiences that ask a viewer to question, doubt, and perhaps explore trust.

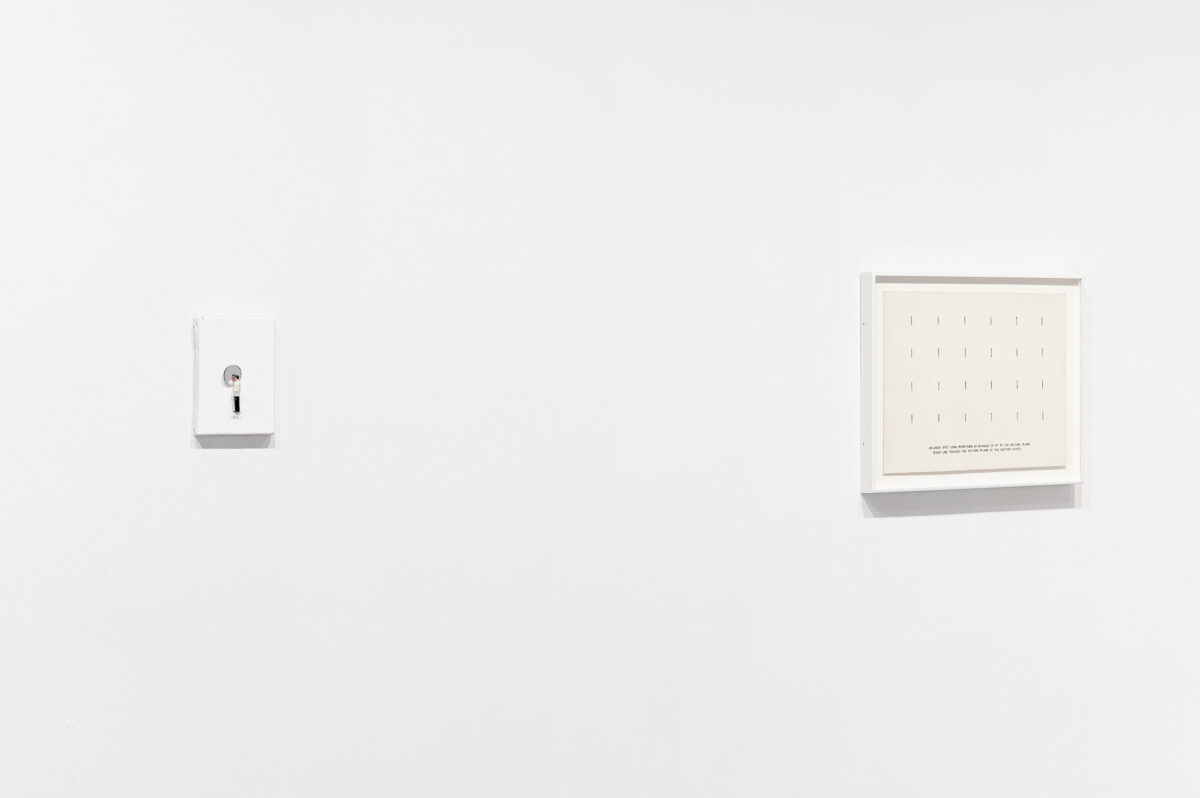

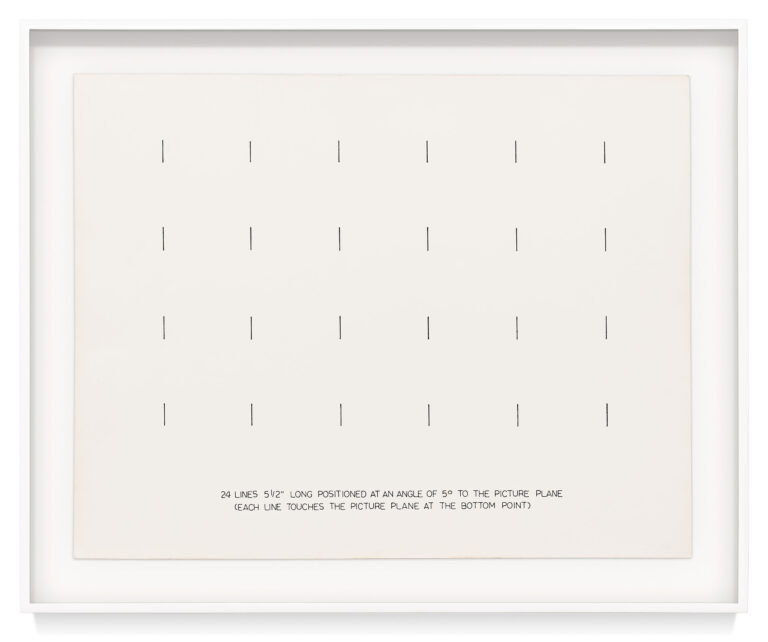

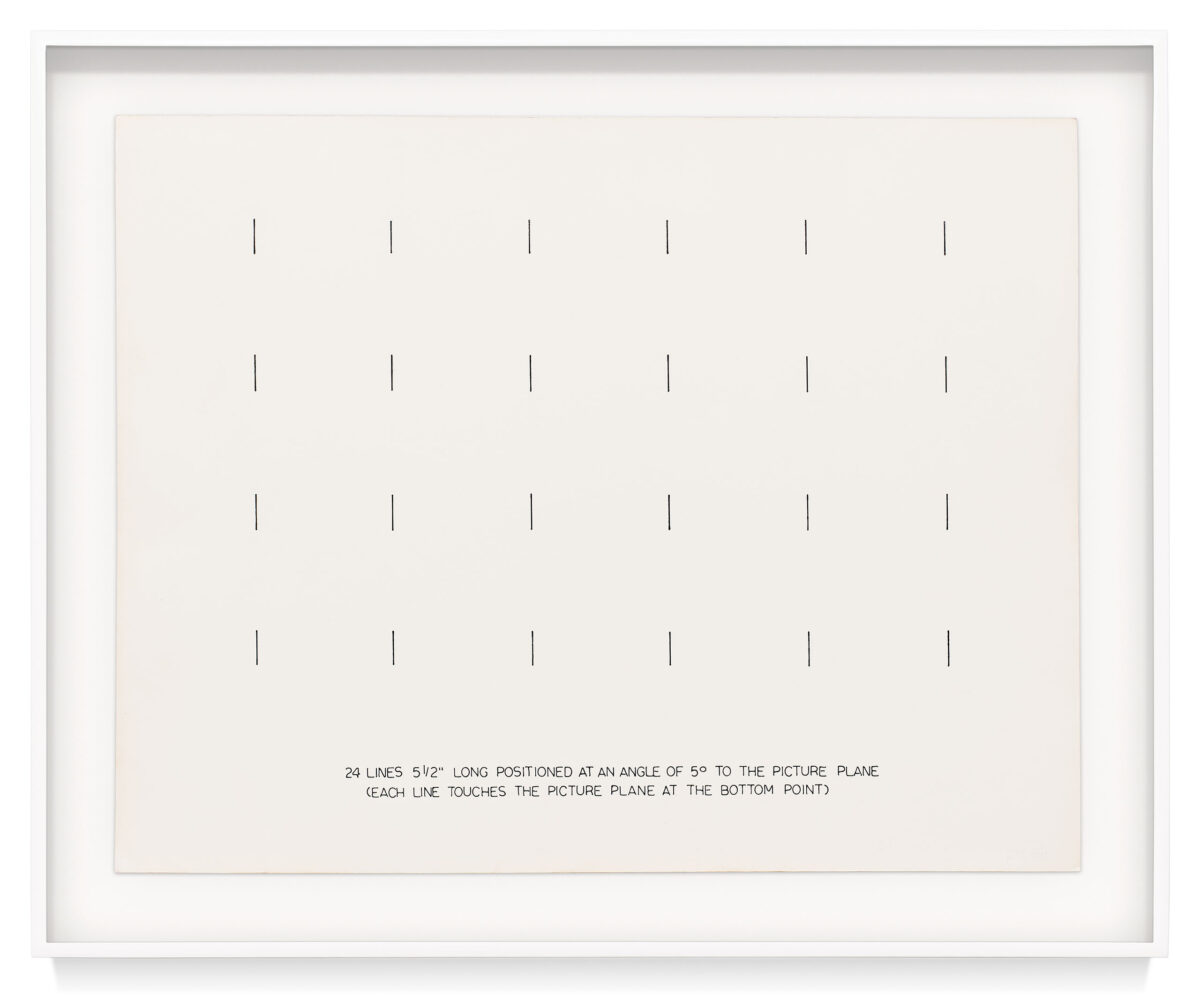

As an example, a 1968 piece in the current exhibition displays a grid of 24 lines that are seemingly identical. However, Huebler’s caption/title reads, “24 LINES 5 1/2” LONG POSITIONED AT AN ANGLE OF 5º TO THE PICTURE PLANE (EACH LINE TOUCHES THE PICTURE PLANE AT THE BOTTOM POINT).” With a bit of thinking, a viewer recognizes that the lines are actually far shorter than 5” long but without the text, a viewer would have no way of knowing that Huebler has used foreshortening. Even with the text as explanation, one most likely still wonders whether the text is accurate. With no way to prove or disprove, the piece engages a viewer in questioning representation, subjectivity, and factuality. While made around 50 years ago, the works presciently speak to the current problematics of large language models and AI.

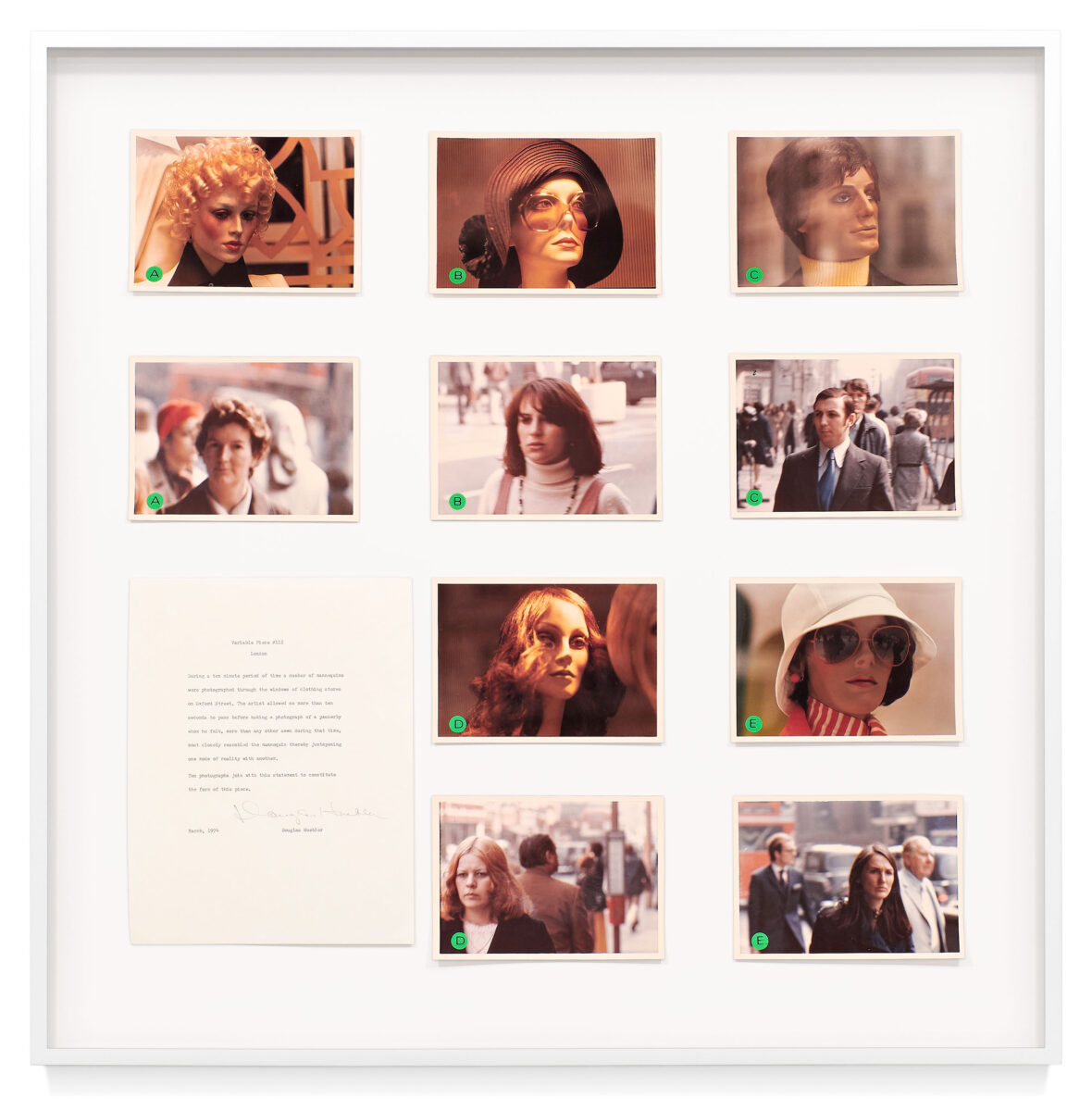

As a slightly later example, “Variable Piece #112 London”(1974) presents ten photographs, in five pairs denoted with letter-matching stickers. One of each pair is a photograph of a mannequin; the second is of an actual person. The connection perhaps could be guessed, but to a casual viewer it is unknown. The accompanying text states:

During a ten minute period of time a number of mannequins were photographed through the windows of clothing stores on Oxford Street. The artist allowed no more than ten seconds to pass before making a photograph of a passerby whom he felt, more than any other seen during that time, most closely resembled the mannequin thereby juxtaposing one mode of reality with another. Ten photographs join with this statement to constitute the form of this piece.

As in the previously mentioned work, a viewer can take a leap of faith and begin to see what Huebler guides one to do, or one can doubt. The choice is, of course, open but by trusting the text, a viewer can see through another’s impressions. Huebler has created balance in the work between the photographer’s perception as he responds to the constraints laid out for the work and the opportunity for a viewer to “make the leap” to “understand” how the artist saw the connections. Openness and direction are equally important in the act of exploration for the artist and the viewer.

Liliana Porter (b. 1941, Buenos Aires, Argentina, lives in New York City and Rhinebeck, New York), like Huebler, came to prominence in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Initially known for her activities with the New York Graphic Workshop, Porter made work that balanced between the use of trompe-l’oeil and empty visual space so as to allow a viewer’s imagination to complete an image. Using actual and painted shadows, physical scratches made by images of nails, and images of wrinkles on flat and on wrinkled paper provided the artist with a wealth of opportunities to confuse and delight a viewer. Over time, Porter’s imagery became less dry and her use of quotations from the realm of commercial production (postcards, well-used toys, etc.) increased. Playfulness took center stage and more emotional room became available for the audience to imagine a fuller narrative.

In the currently exhibited “To Go Back, Woman in White” (2019) Porter presents a small found figurine standing on what appears to be a simple winding path (what is actually just two parallel lines) that ends at the base of a mug, upon which she has drawn a continuation of the lines and has them end at the image of the door of a small house on the mug. All of this is sitting upon a small shelf with a softly-curving, irregular front edge. Who is the figure? What do they feel? What is the path like? Does the figure want to go home? Is the house home? All of these questions (and more) are both asked and oftentimes answered by a viewer. At this point, it’s important to pause and recognize that the viewer is asking these questions of a figurine on a spare shelf where it shares space with a mug. Self-awareness, along with empathy and imagination seem to be key for Porter as an artist. The work she makes provides a platform for viewers to appreciate those emotional and mental states all while plainly showing the homeliness of her materials and the importance of openness.

“Weaver with Black Hair” (2021) positions the small found figurine right at the edge of the work’s boundaries, her legs swinging over the lip of a long shelf. Here Porter takes a woman in put-together, yet anonymous attire and with the addition of two sewing needles, engages her in an ongoing process with the heap of textile material piled to her side and spilling off the shelf. The frozen tableau offers the viewer entry to many narratives, depending on their interpretation of who the figure might be and what she is making (or undoing). A neat storyline is not the artist’s concern here; her role begins and end with sketching the relationships between the elements of the work and the viewer. As in the other exhibited works, Porter’s engagement with still objects on the smallest scale opens up a vast horizon of possibilities over undefined time.