“What we take as a finished fact, this image of a landscape, of a garden, as we see it here, in fact is always a willful construction, not of rational thinking, but of this element of us that needs to try to make sense of the world … And what that suggests is that the way of apprehending the world, we all have to do, making sense of fragments, saying we understand history and what we do is we take different fragmentary stories and pieces of facts and dates and construct a possible history.”

–William Kentridge

For artist William Kentridge, mishearing is a key creative and philosophical principle, representing the way the human mind constructs meaning from uncertainty. In Kentridge’s practice, misunderstanding and mistranslation are not failures, but fruitful moments that generate new ideas and narratives. In an often-told story, Kentridge, as a child, misunderstood about his father’s work as a defense attorney for Nelson Mandela in the South African Treason Trial (1956–1961). Kentridge misheard it as “trees and tiles” due to a mosaic-tiled table and the fir trees at his family home. This memory became a powerful metaphor for understanding the world through fragments and pieces, connecting the private experience of childhood to the public sphere of political events.

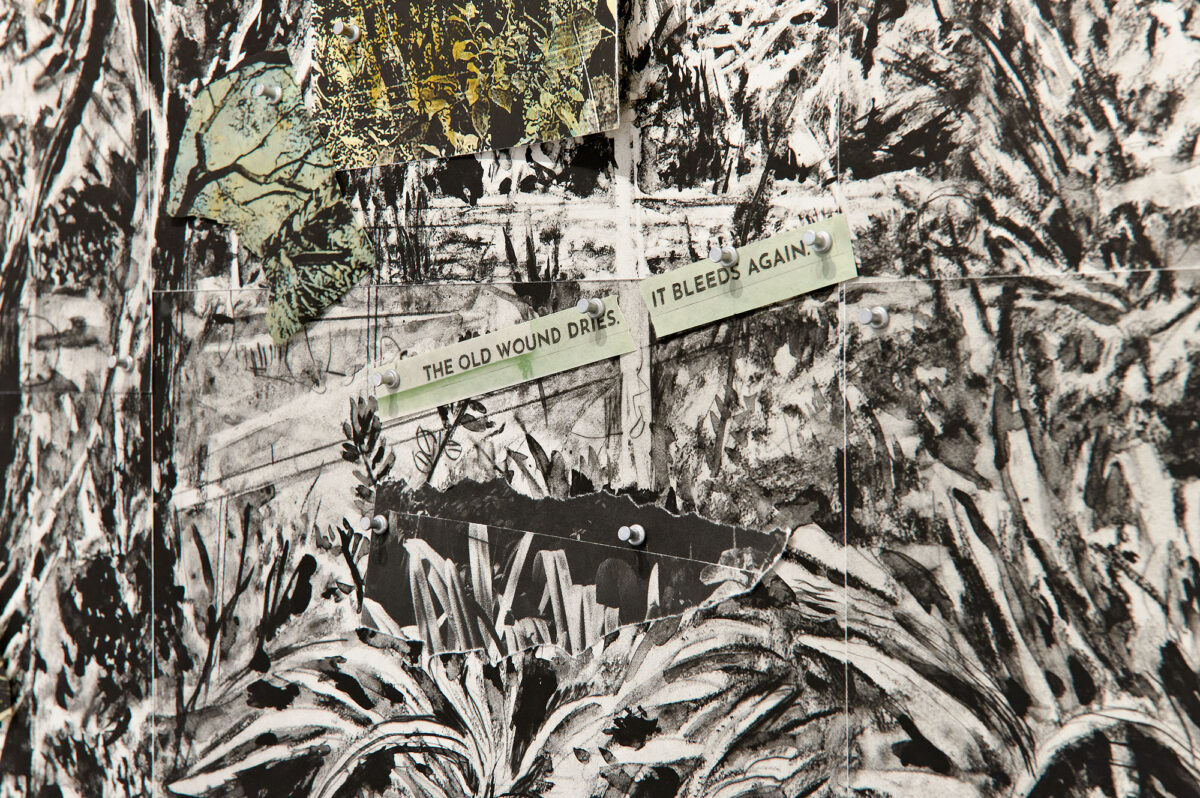

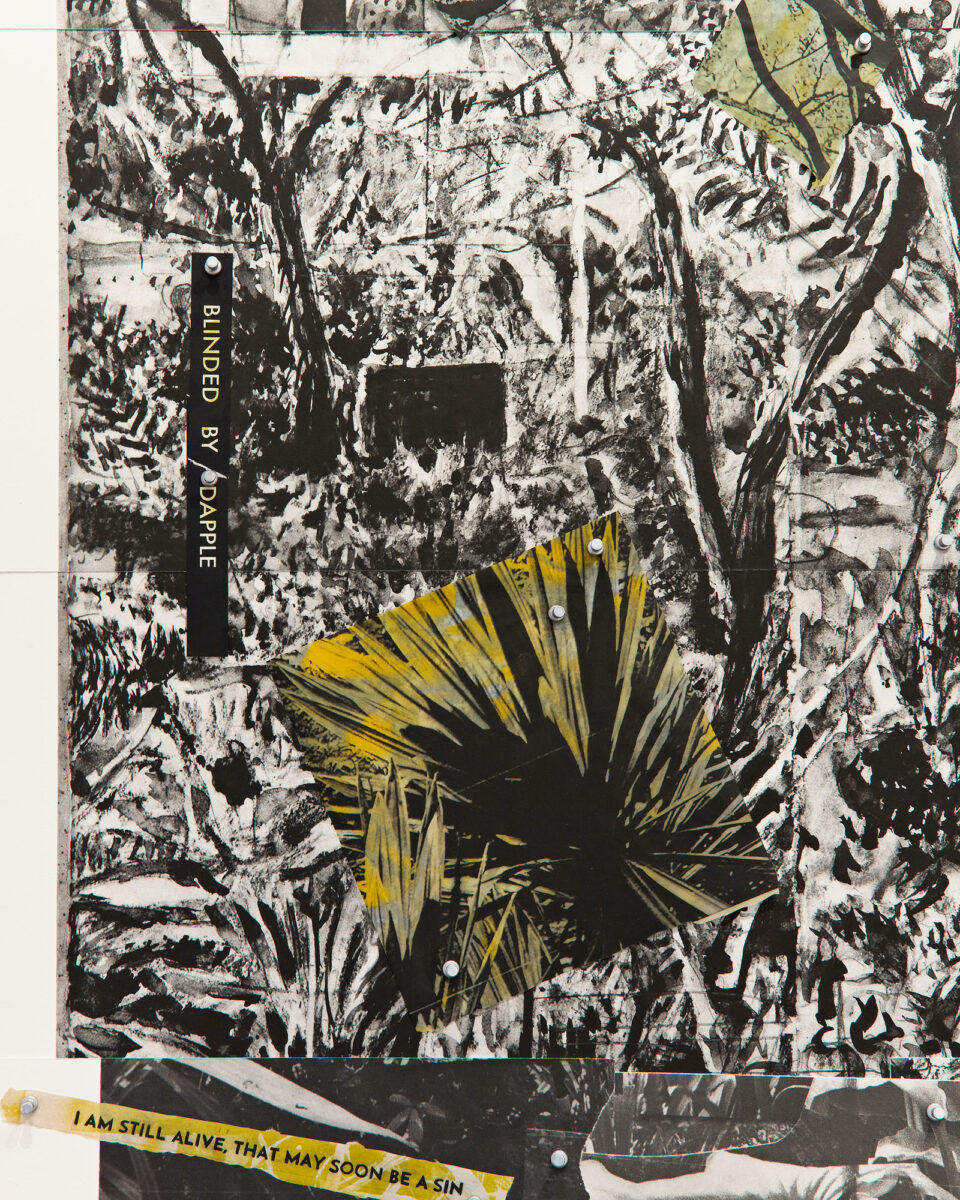

In Kentridge’s distinctive tree and garden works, individual sheets of paper are assembled like tiles to form the overall images, often incorporating fragmented texts. The scenes represent not just the nature depicted, but also the complexities of knowledge and history, as well as concepts of growth, decay, and interconnectedness. The spaces depicted also serve as a canvas for fragmented texts, drawn from literature and poetry, further reinforcing the idea of a multi-faceted understanding of history, memory, and the world at large.

The work currently on view at Krakow Witkin Gallery, “How to Explain Who I Was,” is the latest of the artist’s large-scale works to challenge notions of veracity, completeness, and comprehension. By employing numerous different methods of reproduction (photography, photogravure, photopolymer, and drypoint etching) onto 52 sheets of seven different types of paper collaged and pinned together, Kentridge has created a scenario where various types of distinct marks, imagery, size, image source, and paper are considered equally. Photos of pins holding a piece of paper in the studio have the same relevance as actual pins holding the exhibited piece together. A photogravure of a photograph of a charcoal and India ink drawing is overlayed with direct drypoint marks. Like in much of Kentridge’s work, “reality” is subjective, incomplete, reformulated, and expanded in poetic ways where parts, parts left out, and the sum of the parts are equally significant.

“It shows that the uncertainty and the doubt that is central to the studio practices are also ways of understanding the limitations of our understanding of the world and our certainties about the world, and makes a long-term argument for doubt, for being careful about being too certain on any judgments and understanding that all of these understandings of all of our understanding of different parts of the world are constructions that we make from incomplete fragments.”

–William Kentridge