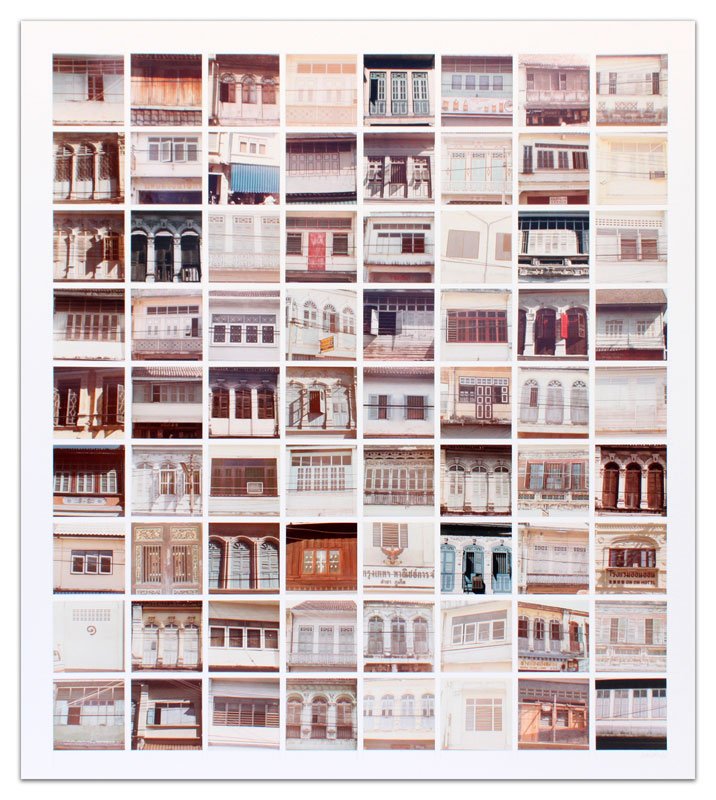

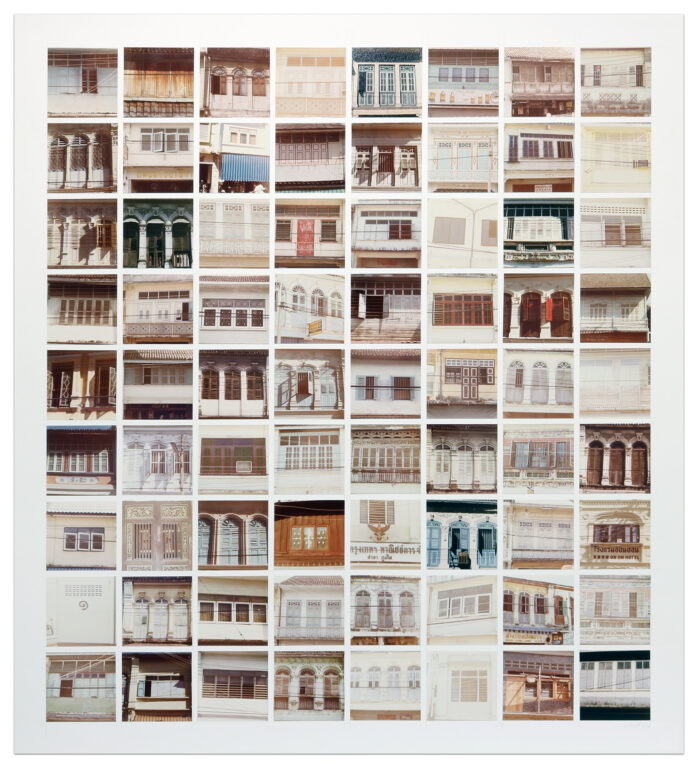

Windows

1980

Seventy-two photographs mounted on one board

Each image size: 3 1/4 x 3 1/4 inches each (8.3 x 8.3 cm each)

Composite image size: 31 1/4 x 27 3/4 inches (79.4 x 70.5 cm)

Paper size: 34 1/4 x 30 3/4 inches (87.6 x 77.5 cm)

Frame size: 35 3/4 x 32 1/4 inches (90.8 x 81.9 cm)

Edition of 20

Signed and numbered lower right in graphite

(Inventory #32371)

Sol LeWitt

Windows

1980

Seventy-two photographs mounted on one board

Each image size: 3 1/4 x 3 1/4 inches each (8.3 x 8.3 cm each)

Composite image size: 31 1/4 x 27 3/4 inches (79.4 x 70.5 cm)

Paper size: 34 1/4 x 30 3/4 inches (87.6 x 77.5 cm)

Frame size: 35 3/4 x 32 1/4 inches (90.8 x 81.9 cm)

Edition of 20

Signed and numbered lower right in graphite

(Inventory #32371)