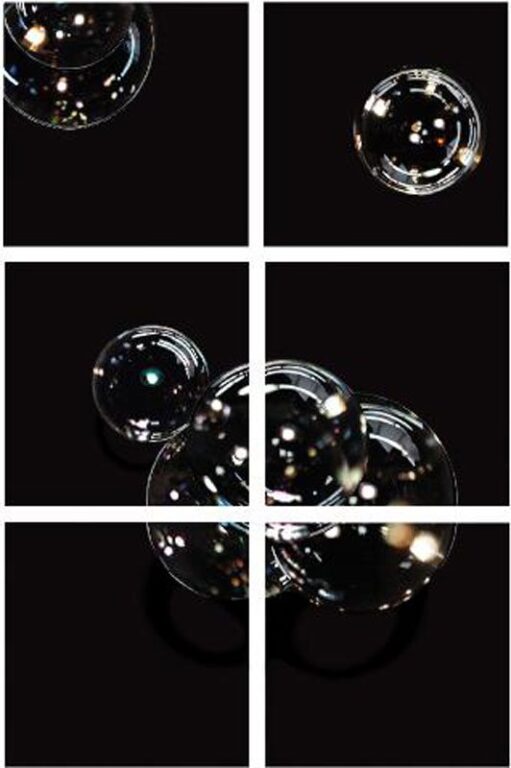

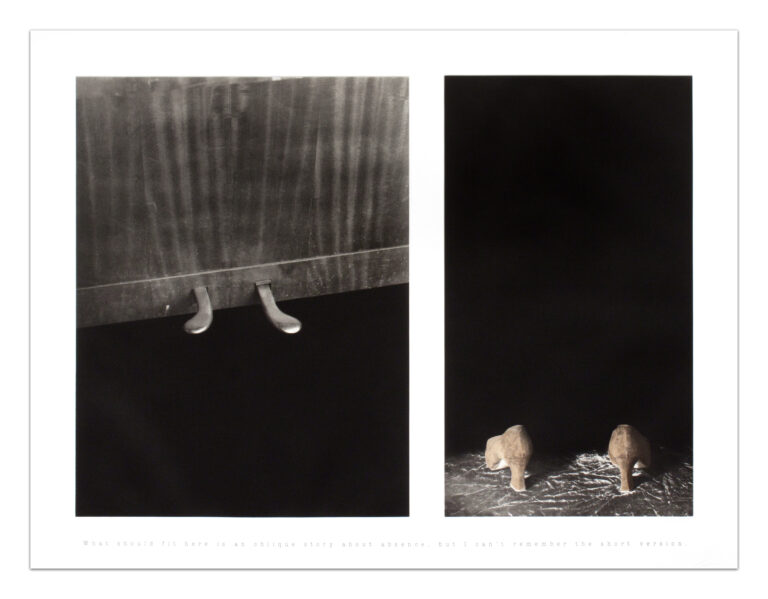

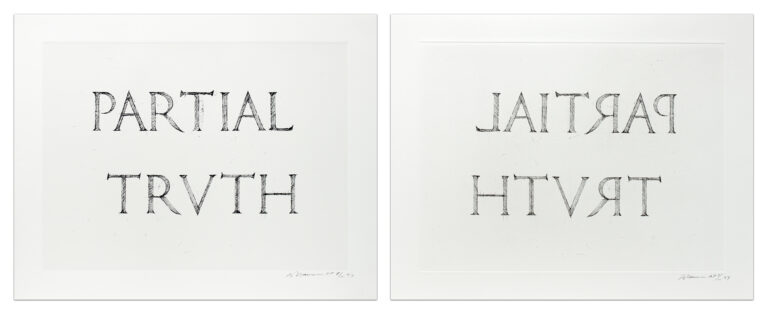

Dialogue (with Bottle Opener)

1995

Silver gelatin prints in three parts

Edition of 5

Overall size: 11 x 25 3/8 inches (27.9 x 64.5 cm)

Image/paper size: 11 x 8 1/2 inches each (27.9 x 21.6 cm each)

Signed, titled, dated, and numbered on reverse on sheet III

(Inventory #31863)

Liliana Porter

Dialogue (with Bottle Opener)

1995

Silver gelatin prints in three parts

Edition of 5

Overall size: 11 x 25 3/8 inches (27.9 x 64.5 cm)

Image/paper size: 11 x 8 1/2 inches each (27.9 x 21.6 cm each)

Signed, titled, dated, and numbered on reverse on sheet III

(Inventory #31863)