Featuring works by

Josef Albers, Barbara Broughel, John Cage,

Vija Celmins, and Sol LeWitt

Defining “space” is a challenge. Is one referring to the outer space of galaxies ‘far far away’, the inner space of one’s own thoughts and emotions, the space being the distance between the screen you are reading this on and where your eyes are, or in the 21st century, the relatively new cyber-space through which these words were transmitted? The five artists in this show have taken the questions of representation and space and have gone different routes that share visual affinities.

In 1950, having already long ago taught at the Bauhaus and even having moved on from teaching at Black Mountain College to lead the art department at Yale, Josef Albers made four industrial-era engravings (the engravings were made from machine-engraved brass plates). Using a combination of vertical, horizontal and diagonal lines presented in only two widths, Albers simultaneously creates and refutes representations of three dimensions in two dimensions.

In 1958, John Cage composed “Fontana Mix”, a work for magnetic tape that requires reading a score to manipulate the 17 minutes of recorded sound. The score consists of sheets of paper and transparencies. Drawings of differentiated (as to thickness and texture) curved lines are on the sheets of paper. Most of the transparencies have randomly distributed dots, one transparency has a grid and one has a straight line. When they are all overlayed (in a chance-derived way), a performer reads this score by examining the horizontal and vertical intersections of the straight line with the grid and the curved line so as to see a time-bracket along with an understanding of actions to be made. From the outside, this certainly is a convoluted and dense process, but if one steps back from the specifics and recognizes the ethos behind it – one can admire the experimental nature of the composition, score and even performance and/or recording of the work. Seeing that Cage’s approach was one of looking at many possibilities as equal, it is only consistent that he would take the elements of the score and make a version to view, thus twenty three years after composing the piece, Cage revisited the score, enlarging it so as, this time, to make a work for an audience to view, not just to hear.

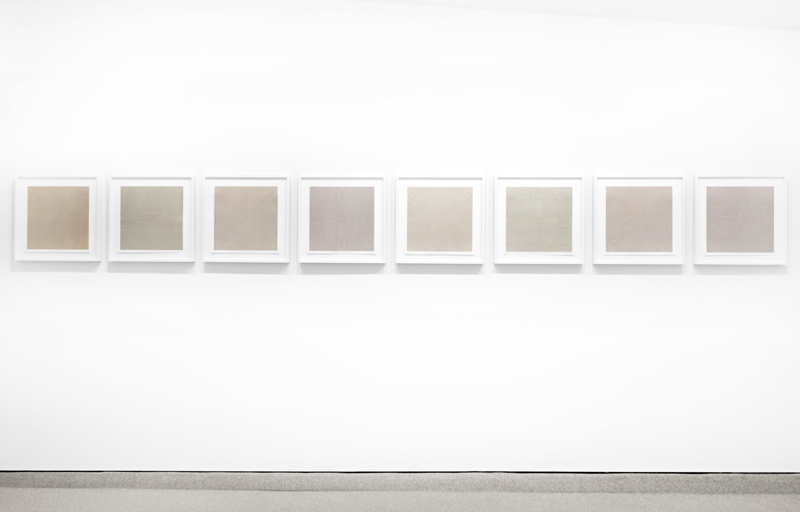

In 1972, Sol LeWitt created a portfolio of eight screenprints titled “Arcs, Circles and Grids”. Each work within the series is a different combination of overlayed lines, but as opposed to Cage’s chance arrangements of dots, grids and curves, LeWitt displayed an affinity for systematic investigation through a specific set of variations. Each version has a unique combination of differently located set of concentric circles, arcs from corners and/or sides and an overall grid. When looked at from a distance, each of the eight is a distinct monochromatic color, yet when observed closely, the intricate combination of the aforementioned lines simultaneously creates both depth and flatness, all through the activity of moire patterns.

In 1991, Vija Celmins created a linoleum cut using her iconic imagery of a night sky. For this work, she carved directly into the block, creating small circles of varying sizes, all with minutely irregular edges. Some circles are closely grouped, others have more space, while others are overlapping so as to create irregular forms. Amongst these ‘dots’ is one seemingly out-of-place mark – a diagonal line with much stronger definition at one end than the other. Looking at the composition abstractly, this line seems incredibly out of place, but amazingly, the mark serves the opposite function when viewed as a figurative image – all those circles become stars and the line becomes a comet.

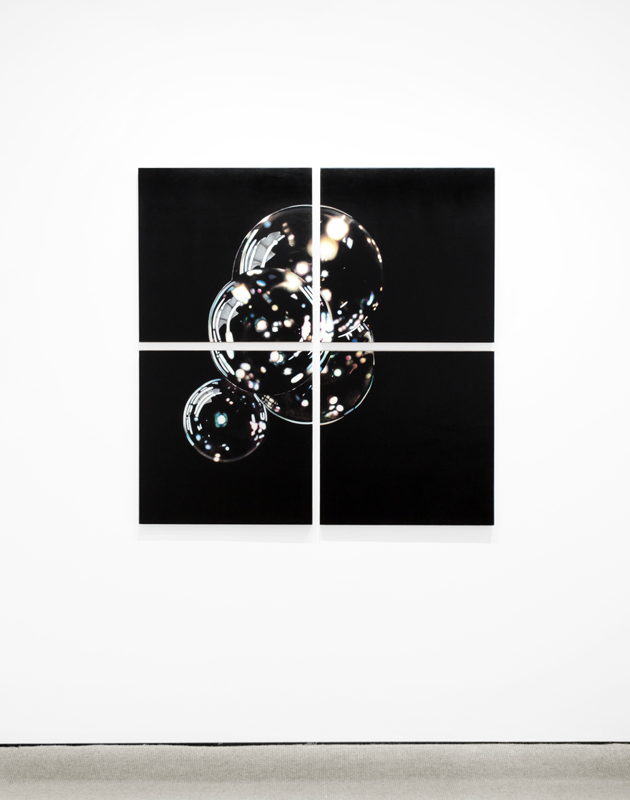

Lastly, Barbara Broughel’s Broken Bubbles, from 2012, examines the history of abstraction in one of its possible birthplaces (circa 1700’s Northern Europe) through the depiction, not only of a period-related subject – bubbles – but of the process and materials of rendering (Broughel used pigments and wood that would have been used at that time). What is unconventional, or even radical for the period (but appropriate for this exhibition) is the composition and the way it fractures the realism of the image through leaving the grid visible (thus it references the tool which allows for that realism).

The exhibition, Inner Space, aims to present visually compatible works that explore related but also discrete approaches to looking at the reasons and results of putting line, shape and color to a surface.

Image size: 13 7/8 x 13 7/8 inches each (35.2 x 35.2 cm each)

Paper size: 14 7/8 x 14 7/8 inches each (37.8 x 37.8 cm each)

Frame size: 18 7/8 x 18 7/8 inches each (47.9 x 47.9 cm each)

Edition of 100

Signed lower right and numbered lower left on each sheet

(Inventory #17001)

Krakow 1972.03

Available as a complete set only

Image size: 13 7/8 x 13 7/8 inches each (35.2 x 35.2 cm each)

Paper size: 14 7/8 x 14 7/8 inches each (37.8 x 37.8 cm each)

Frame size: 18 7/8 x 18 7/8 inches each (47.9 x 47.9 cm each)

Edition of 100

Signed lower right and numbered lower left on each sheet

(Inventory #17001)

Krakow 1972.03

Available as a complete set only

Image size: 14 1/4 x 16 3/4 inches (36.2 x 42.5 cm)

Paper Size: 20 1/2 x 22 7/8 inches (52.1 x 58.1 cm)

Edition of 80 and 10 HCSigned “V.Celmins” lower right and numbered lower left in graphite

(Inventory #28257)

Image size: 14 1/4 x 16 3/4 inches (36.2 x 42.5 cm)

Paper Size: 20 1/2 x 22 7/8 inches (52.1 x 58.1 cm)

Edition of 80 and 10 HCSigned “V.Celmins” lower right and numbered lower left in graphite

(Inventory #28257)

Image/plate size: 7 1/8 x 9 1/2 inches (18.1 x 24.1 cm)

Paper size: 11 x 15 1/2 inches (27.9 x 39.4 cm)

Frame size: 14 1/4 x 16 1/2 inches (36.2 x 41.9 cm)

Edition of 20

Signed and dated “Albers 50” lower right. Titled and numbered lower left

(Inventory #28124)

Image/plate size: 7 1/8 x 9 1/2 inches (18.1 x 24.1 cm)

Paper size: 11 x 15 1/2 inches (27.9 x 39.4 cm)

Frame size: 14 1/4 x 16 1/2 inches (36.2 x 41.9 cm)

Edition of 20

Signed and dated “Albers 50” lower right. Titled and numbered lower left

(Inventory #28124)

Image/plate size: 7 1/8 x 9 7/16 inches (18.1 x 24 cm)

Paper size: 12 x 15 1/2 inches (30.5 x 39.4 cm)

Edition of 20

Signed and dated “Albers 50” lower right. Titled and numbered lower left

(Inventory #28125)

Image/plate size: 7 1/8 x 9 7/16 inches (18.1 x 24 cm)

Paper size: 12 x 15 1/2 inches (30.5 x 39.4 cm)

Edition of 20

Signed and dated “Albers 50” lower right. Titled and numbered lower left

(Inventory #28125)

Image/plate size: 7 1/8 x 9 7/16 inches (18.1 x 24 cm)

Paper size: 12 x 15 1/2 inches (30.5 x 39.4 cm)

Edition of 20

Signed and dated “Albers 50” lower right. Titled and numbered lower left

(Inventory #28126)

Image/plate size: 7 1/8 x 9 7/16 inches (18.1 x 24 cm)

Paper size: 12 x 15 1/2 inches (30.5 x 39.4 cm)

Edition of 20

Signed and dated “Albers 50” lower right. Titled and numbered lower left

(Inventory #28126)

Image/plate size: 7 1/8 x 9 7/16 inches (18.1 x 24 cm)

Paper size: 12 x 15 1/2 inches (30.5 x 39.4 cm)

Edition of 20

Signed and dated “Albers 50” lower right. Titled and numbered lower left

(Inventory #28127)

Image/plate size: 7 1/8 x 9 7/16 inches (18.1 x 24 cm)

Paper size: 12 x 15 1/2 inches (30.5 x 39.4 cm)

Edition of 20

Signed and dated “Albers 50” lower right. Titled and numbered lower left

(Inventory #28127)

Panel size: 24 x 24 x 1 inches each (61 x 61 x 2.5 cm each)

Overall size: 49 1/2 x 49 1/2 x 1 inches (125.7 x 125.7 x 2.5 cm)

Signed, titled and dated on reverse on each panel

(Inventory #25602)

Panel size: 24 x 24 x 1 inches each (61 x 61 x 2.5 cm each)

Overall size: 49 1/2 x 49 1/2 x 1 inches (125.7 x 125.7 x 2.5 cm)

Signed, titled and dated on reverse on each panel

(Inventory #25602)

Edition of 42

Signed and numbered on bottom

8 x 8 x 8 inches (20.3 x 20.3 x 20.3 cm)

(Inventory #27856)

Edition of 42

Signed and numbered on bottom

8 x 8 x 8 inches (20.3 x 20.3 x 20.3 cm)

(Inventory #27856)

Image size: 19 1/2 x 27 1/2 inches (49.5 x 69.9 cm)

Paper size: 22 1/2 x 30 inches (57.2 x 76.2 cm)

Frame size: 26 x 33 3/4 inches (66 x 85.7 cm)

Edition of 97

Signed and dated ‘John Cage 1981’ lower right and numbered lower left in pencil

(Inventory #27854)

Image size: 19 1/2 x 27 1/2 inches (49.5 x 69.9 cm)

Paper size: 22 1/2 x 30 inches (57.2 x 76.2 cm)

Frame size: 26 x 33 3/4 inches (66 x 85.7 cm)

Edition of 97

Signed and dated ‘John Cage 1981’ lower right and numbered lower left in pencil

(Inventory #27854)

No results found.

10 Newbury Street, Boston, Massachusetts 02116

617-262-4490 | info@krakowwitkingallery.com

The gallery is free and open to the public. Please note our summer schedule:

June

Tuesday – Saturday, 10–5:30

(Open on Juneteenth)

July 1–25

Tuesday – Friday, 10–5:30

(Closed Friday, July 4)

July 29 – September 1

Open via appointment

Beginning September 2

Tuesday – Saturday, 10–5:30