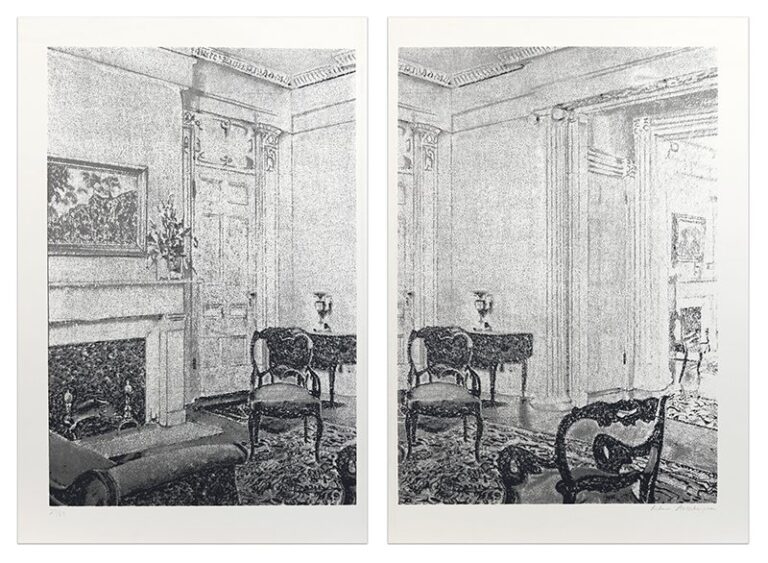

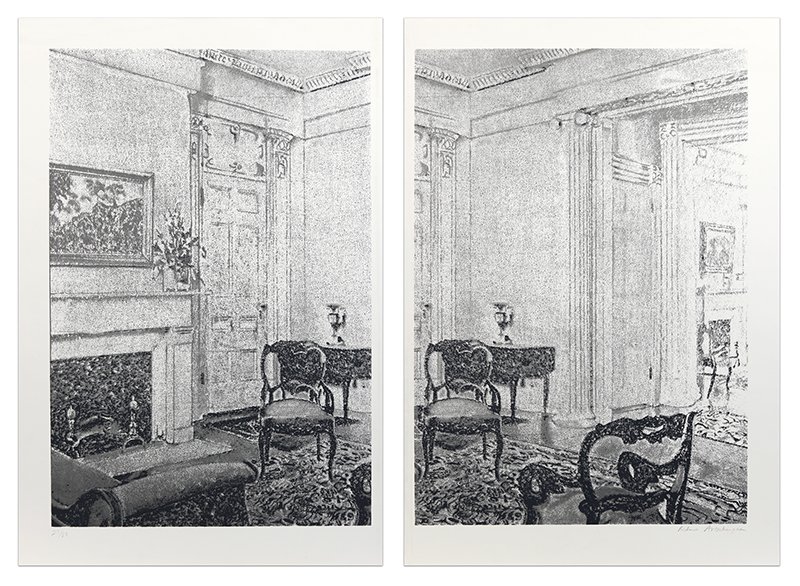

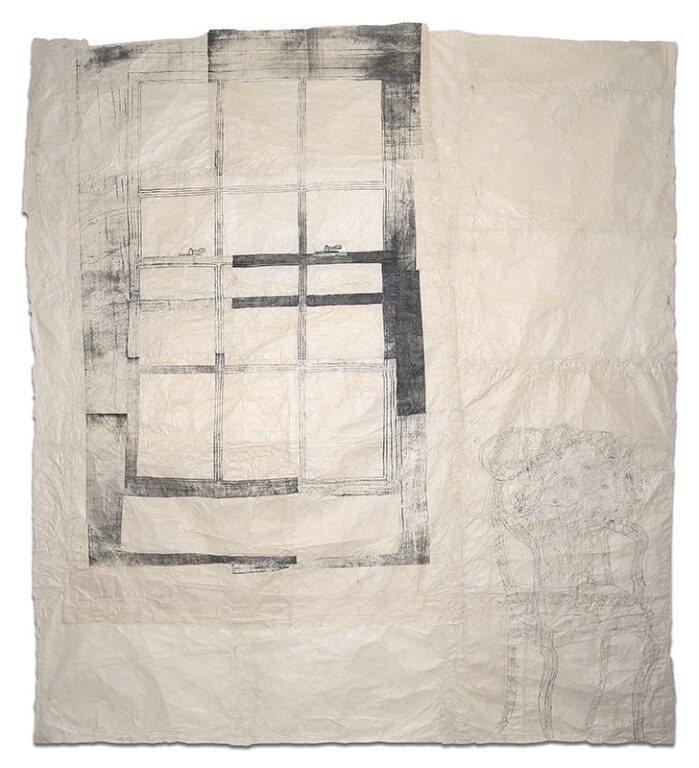

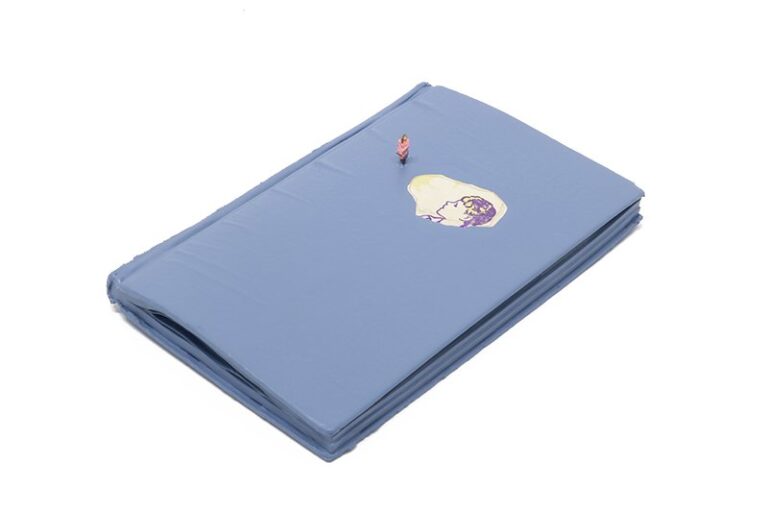

Interior

1972

Screenprint in colors on Wove paper on two sheets

Edition 27 of 83, this being a unique variant, altered by the artist

Overall size approximately: 32 3/4 x 44 3/8 inches (83.2 x 112.7 cm)

Signed lower right and numbered lower left in graphite

(Inventory #30890)

Richard Artschwager

Interior

1972

Screenprint in colors on Wove paper on two sheets

Edition 27 of 83, this being a unique variant, altered by the artist

Overall size approximately: 32 3/4 x 44 3/8 inches (83.2 x 112.7 cm)

Signed lower right and numbered lower left in graphite

(Inventory #30890)