66 15/16 x 25 3/16 x 11 inches inches (170 x 64 x 28 cm)

Signed on bottom

(Inventory #29528)

When asked for his thoughts on his 1998 work, “Fiona tights,” Julian Opie wrote the following:

Looking for a language with which to draw the human figure, I came across a set of lavatory door signs. This gave me a basic format to draw with that I then applied to images of friends and neighbours. Looking back it seems I was sorting out the rules for many future works and projects, but at the time I just wandered in fairly casually asking people to take any old pose in the outfit they happened to be wearing and photographing them front on. A single logo-like image of each individual My main aim was to have images to make into two-sided statues of people. These, I would mix in with the statues of animals and cars and buildings that I had been using to build mixed composition exhibitions. A kind of indentikit 3D form of making an interchangeable art installation a bit like a children’s game where you make a town or farm scene.

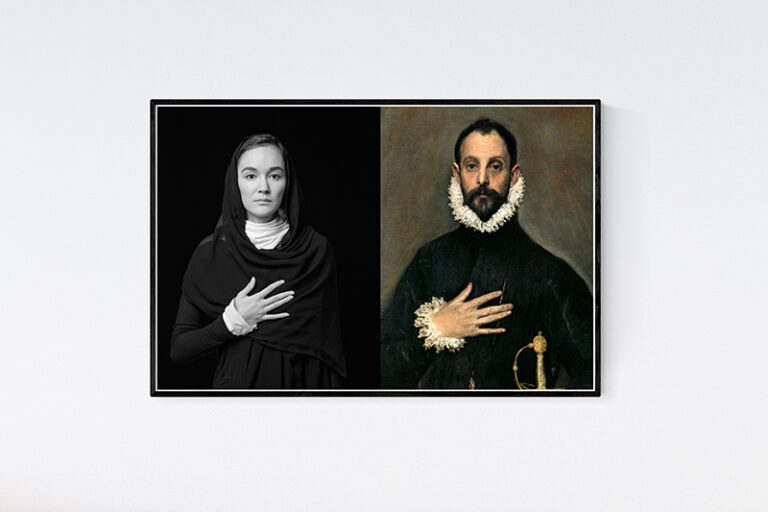

Having built a small library of people to use in this way, I then started to realise that these “people statues” had a stronger sense of individuality and character than the other more generic objects and could be perhaps used in different and stand-alone ways. I conceived a project that instead of having a mix of objects or even a mix of people, would have the same person in various poses and outfits. The first poses had come about naturally but began to remind me of portrait poses in old master paintings, while the various outfits seemed to suggest clothing catalogues or shop window displays. I asked a stylish friend of mine to undertake the project and she patiently put on all her different outfits including casual, formal and even sport clothes, accompanied by all the standing poses we could think of for each outfit. It took quite a while and led to statues, large and small.

I like it when the internal logic of a project dictates the results.

Julian Opie

66 15/16 x 25 3/16 x 11 inches inches (170 x 64 x 28 cm)

Signed on bottom

(Inventory #29528)

When asked for his thoughts on his 1998 work, “Fiona tights,” Julian Opie wrote the following:

Looking for a language with which to draw the human figure, I came across a set of lavatory door signs. This gave me a basic format to draw with that I then applied to images of friends and neighbours. Looking back it seems I was sorting out the rules for many future works and projects, but at the time I just wandered in fairly casually asking people to take any old pose in the outfit they happened to be wearing and photographing them front on. A single logo-like image of each individual My main aim was to have images to make into two-sided statues of people. These, I would mix in with the statues of animals and cars and buildings that I had been using to build mixed composition exhibitions. A kind of indentikit 3D form of making an interchangeable art installation a bit like a children’s game where you make a town or farm scene.

Having built a small library of people to use in this way, I then started to realise that these “people statues” had a stronger sense of individuality and character than the other more generic objects and could be perhaps used in different and stand-alone ways. I conceived a project that instead of having a mix of objects or even a mix of people, would have the same person in various poses and outfits. The first poses had come about naturally but began to remind me of portrait poses in old master paintings, while the various outfits seemed to suggest clothing catalogues or shop window displays. I asked a stylish friend of mine to undertake the project and she patiently put on all her different outfits including casual, formal and even sport clothes, accompanied by all the standing poses we could think of for each outfit. It took quite a while and led to statues, large and small.

I like it when the internal logic of a project dictates the results.